💡 Lighting the Way North

Tucked in the remote waters of Lake Superior, just off the northeastern tip of Isle Royale, Passage Island Lighthouse blazed to life for the first time on July 1, 1882. It stands as the northernmost lighthouse in the United States. The lighthouse’s powerful beam served as a crucial guidepost for ships navigating the narrow, treacherous passage between Isle Royale and the Canadian shore. But the story of how this iconic light came to be is as rugged and resilient as the rocky outcrop it rests upon.

In the late 1860s and early 1870s, copper and silver mining on Lake Superior’s north shore—particularly the wildly successful Silver Islet mine near present-day Thunder Bay—led to a surge in maritime traffic. Vessels made their way to and from the lower Great Lakes through a narrow, deep-water channel. The channel between Isle Royale and Passage Island is a dangerous route. Recognizing this, the U.S. Lighthouse Board began requesting funds in 1871 to construct a lighthouse on Passage Island. Despite years of appeals, Congress finally authorized the $18,000 appropriation in 1875. But there was a catch. The money would only be released if Canada built a lighthouse on Colchester Reef in Lake Erie. That didn’t happen until 1885, yet somehow, funds were released early in 1880, and construction commenced the following year.

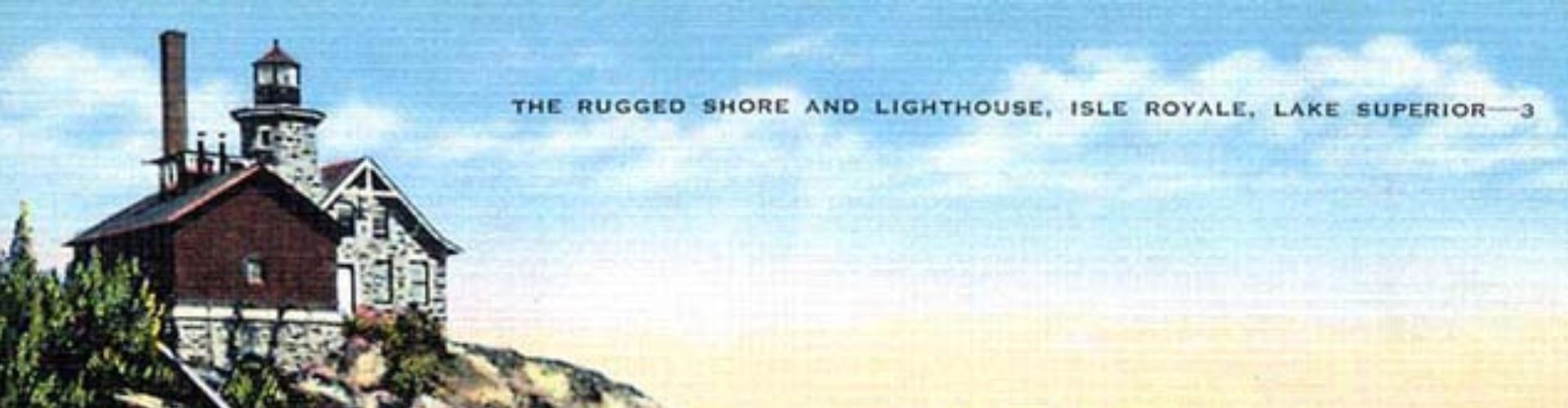

Stone Twin

The lighthouse built was a stone twin of others in the region designed in Gothic Revival Style. Lighthouses like McGulpin Point and Eagle Bluff. The style was a two-story keeper’s dwelling with a square stone tower. The tower was topped by a ten-sided lantern room and a fourth-order Fresnel lens that projected a fixed red light. Positioned high atop a rocky cliff, the beacon sat nearly 100 feet above Lake Superior’s surface. A 1,500-pound fog bell and striking mechanism added sound to sight. Passage Island Lighthouse aided ships even in the thickest weather.

Harsh Conditions

The lighthouse’s first keeper, Richard Singleton, tragically died less than a year into his service. He was struck by a train in Port Arthur while gathering supplies. His family not knowing of his death was stranded and starving at the lighthouse. Thanks to a passing steamer captain they were rescued. The station’s remoteness and harsh conditions required grit and determination from its keepers. Living on Passage Island they faced howling gales and sub-zero temps. During a ferocious storm in 1905 they faced crashing waves 60 feet above the lake.

From rescuing shipwreck survivors to enduring multi-day storms while keeping the fog signal running, the men and women who lived and worked on Passage Island played a vital, heroic role in Great Lakes navigation. Over time, the station saw upgrades: a new lens with a white flash every ten seconds, steam fog signals, electrification, and even a radio beacon and telephone. The lighthouse was automated in 1978 and today is managed by the National Park Service, which offers excursions to this historic outpost from Rock Harbor.

So next time you admire the sweeping views of Lake Superior, take a moment to think of the keepers who kept that light burning—especially on July 1, 1882, when it shone into the darkness for the very first time.

Learn more about the rich history of the Western Upper Peninsula.